Hangar Queens: The Hidden Cost of Aircraft That Never Fly

Published on January 13, 2026 • 5 min read

You've got a 2-year waiting list for hangar space. You've got pilots calling every week asking if anything opened up.

And you've got that Mooney in Bay 12 that hasn't moved in 18 months.

Welcome to the hangar queen problem.

What Exactly Is a Hangar Queen?

In GA slang, a "hangar queen" is an aircraft that spends most of its time sitting instead of flying. These aren't aircraft temporarily down for maintenance or annual inspections. They're planes that have essentially become expensive garage trophies, collecting dust rather than flight hours.

The term originally described military aircraft cannibalized for parts. In civilian aviation, it covers any aircraft that "just sits there and looks good" without regular flight time.

Beautiful aircraft, zero flight hours.

Beautiful aircraft, zero flight hours.

How Common Are Hangar Queens?

The numbers are pretty stark:

| Metric | Data Point | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Average GA aircraft utilization | 95-100 hours/year | FAA GA Survey |

| Typical private pilot flight time | Less than 50 hours/year | AOPA |

| GA aircraft that didn't fly at all (Australia) | 24% of fleet | BITRE Study |

| T-hangar occupancy rate (US average) | 98% | Industry survey |

| Airports with hangar waiting lists | 71% | AOPA Poll |

That's roughly 8 hours of flight time per month for the average piston aircraft. Many go 60, 90, even 180+ days between flights.

At any GA airport, you likely have aircraft that haven't moved since their last annual. Some haven't moved in years.

The Real Math: What a Hangar Queen Costs You

A hangar queen pays rent. And that's about it.

Here's the actual revenue difference between an active tenant and an inactive one:

Active Single-Engine Tenant (Flying 100 hrs/year)

| Revenue Category | Annual Revenue |

|---|---|

| Hangar Rent | $4,800 |

| Fuel (50 gal/month @ $2.50 margin) | $1,500 |

| Oil Changes (4/year @ $150) | $600 |

| Annual Inspection | $800-1,200 |

| Parts & Repairs | $500-1,000 |

| Misc Services | $200-400 |

| Total Annual Revenue | $8,400-$9,700 |

Hangar Queen Tenant (Flying 0 hrs/year)

| Revenue Category | Annual Revenue |

|---|---|

| Hangar Rent | $4,800 |

| Everything Else | $0 |

| Total Annual Revenue | $4,800 |

Revenue gap per hangar queen: $3,600-$4,900/year

That's for a single-engine piston aircraft. For based turboprops or light jets, the gap widens significantly. Active jets generate substantially more in fuel and services.

If you've got 3 hangar queens in your T-hangars, you're leaving $10,000-$15,000/year on the table compared to having active tenants.

When we built AirPlx, we started tracking this data for FBOs. The pattern repeats everywhere. Most operators don't realize how many of their based aircraft are effectively dormant until they see the utilization numbers in black and white.

The Capacity Problem

The revenue gap above assumes you have no waiting list. But most FBOs do, which means every hangar queen is also blocking a paying customer.

DeKalb-Peachtree Airport (KPDK) near Atlanta once had a 7-15 year waitlist for county hangars. Bay Area airports commonly see 10+ year waits. When pilots are waiting that long for hangar space, every inactive aircraft sitting inside represents years of denied access.

When one hangar queen occupies space for a decade, that's a decade of active pilots denied access and a decade of lost ancillary revenue.

Every occupied hangar should be generating revenue beyond just rent

Every occupied hangar should be generating revenue beyond just rent

The Surge Day Problem

During fly-ins, weather emergencies, or peak demand days, you need to shuffle aircraft. Active tenants can be moved, consolidated, or temporarily parked outside.

A hangar queen often can't be moved at all. It may have:

- Flat tires

- Dead batteries

- No prop

- An absent owner

That bay becomes dead space exactly when you need flexibility most. We've seen FBOs turn away transient aircraft during storms because they couldn't shuffle their own hangars, all because two or three based aircraft were physically unmovable.

Real Examples

These aren't hypotheticals. They're documented cases from pilot forums and government audits:

Midwest T-hangar: A Mooney sat untouched for 10 years. The out-of-state owner (living in Florida) paid rent the entire time, ultimately spending more in storage fees than the aircraft was worth. Meanwhile, local pilots sat on the waiting list.

Los Angeles County: A 2024 FAA audit of five GA airports found 24% of 1,089 county-owned hangars were either empty or used for non-aviation storage. Overpriced rents drove away pilots while non-aviation renters paid below-market rates.

Rogers, Arkansas: A Piper PA-18 sat on the ramp for at least 10 years: three flat tires, no propeller, covered in bird droppings. Not technically a hangar queen, but the same operational dead weight.

What FAA Policy Says

For federally-obligated airports (those accepting FAA grants), there's regulatory backing for action.

FAA policy explicitly "permits storage of active aircraft" and aircraft under repair, but not the indefinite storage of non-operational aircraft.

You can require tenants to prove their aircraft is:

- Airworthy, or

- Being actively worked on

If an airplane is just a collection of parts with no intent to fly, the airport can demand the owner remedy the situation or vacate. Many hangar agreements include inspection clauses for this purpose.

Strategies That Work

1. Enforce Airworthy Requirements

Require based aircraft to maintain a current annual inspection. No annual = notice to vacate. This alone filters out the truly abandoned cases.

2. Minimum Fuel Purchase Requirements

Some FBOs have implemented quarterly minimum purchase fees—around $200/quarter. An actively flying piston aircraft easily spends that on fuel. An owner who isn't buying fuel pays the difference as a fee.

This creates a financial incentive: fly more, or subsidize your inactivity.

3. Tiered Pricing

Charge premium rates for month-to-month storage of unflown aircraft versus lower rates for active tenants. Track movement via fuel purchases or simply observe which aircraft never leave their spots.

4. Facilitate Subleases

If an owner only flies a few times per year, encourage them to sublease or share the space. Two aircraft sharing one hangar (one active, one occasional) beats one hangar queen alone.

5. Know Your State Laws

Florida enacted a specific statute: any aircraft idle for more than 45 days or not airworthy is deemed "abandoned or derelict," allowing the airport to start lien and removal proceedings. Many states have similar provisions.

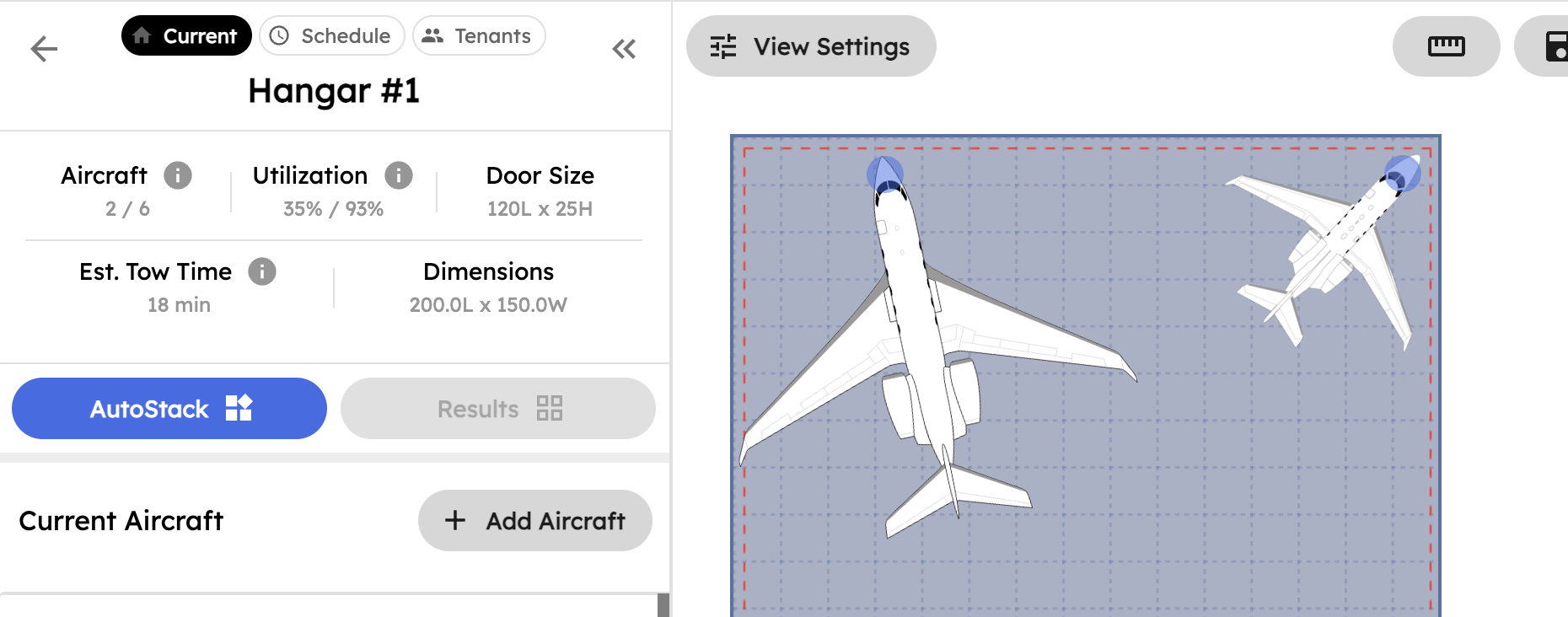

6. Track Utilization Data

Most FBOs don't have good visibility into which aircraft are actually flying. Without data, you're relying on memory and gut feel to identify hangar queens.

One operations manager told us he was shocked to discover that 4 of his 18 T-hangar tenants hadn't purchased fuel in over 6 months. He'd known a couple were "low flyers," but four? That's 22% of his hangar capacity generating rent-only revenue.

Tracking aircraft movement and hangar utilization helps identify inactive tenants before they become decade-long problems

Tracking aircraft movement and hangar utilization helps identify inactive tenants before they become decade-long problems

With proper tracking, you can see exactly which aircraft haven't moved in 30, 60, or 90 days—and have the data to back up conversations with owners. It's a lot easier to say "our records show your Bonanza hasn't flown since March" than "hey, we noticed your plane never moves."

The Bigger Picture

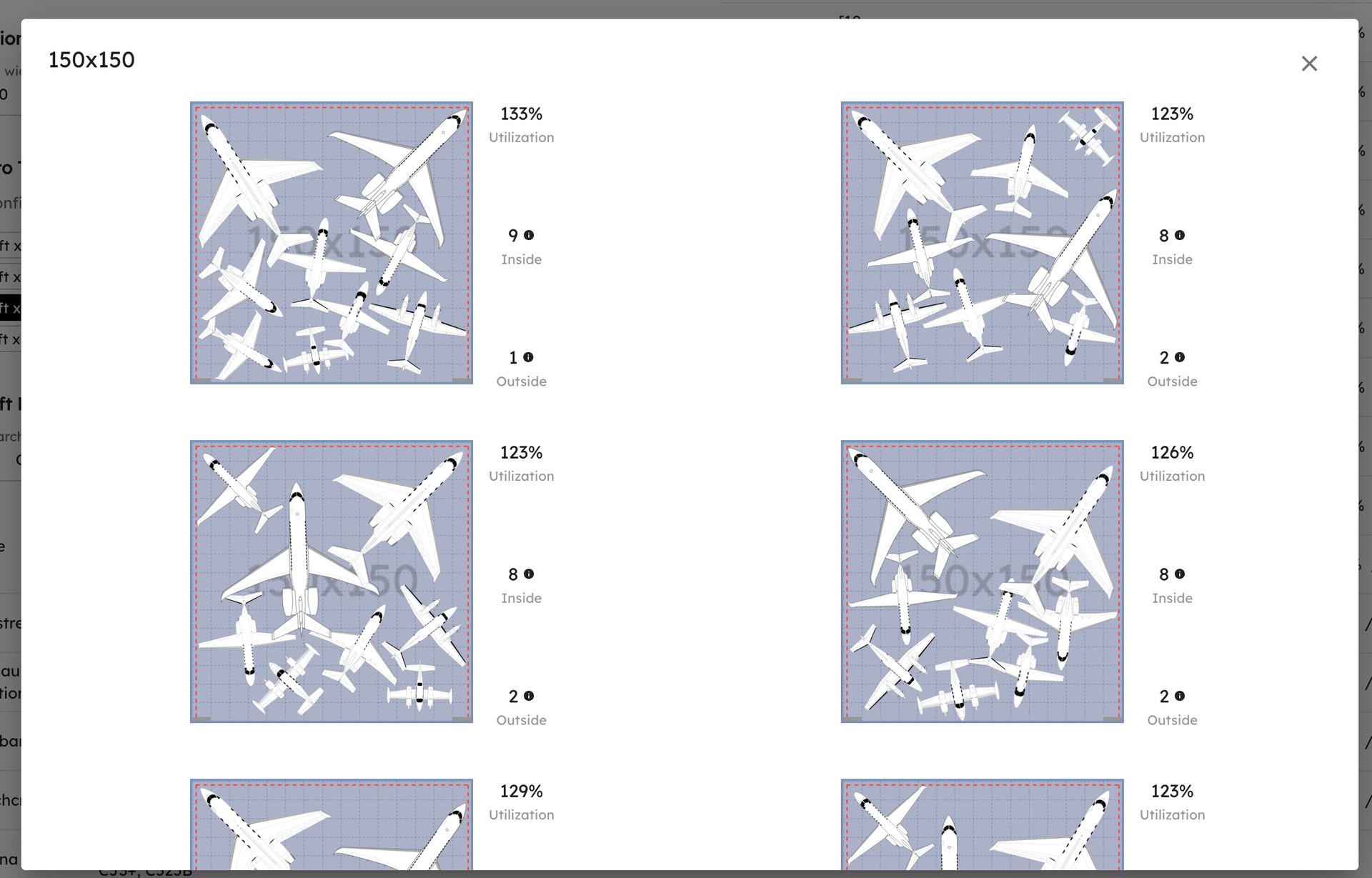

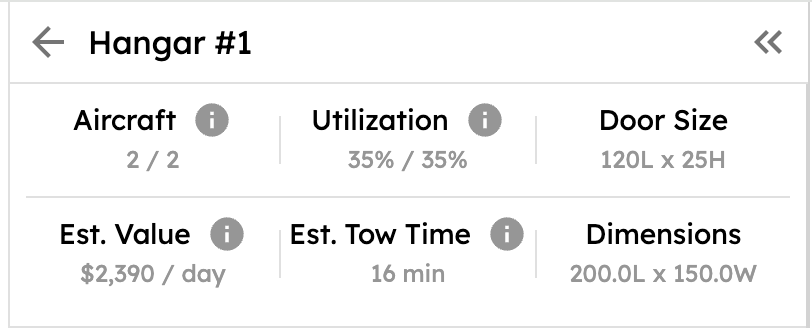

The hangar queen problem connects to a larger challenge: optimizing limited hangar capacity.

Even with some inactive tenants, you can maximize revenue by:

- Stacking aircraft more efficiently in shared hangars

- Using 3D aircraft stacking to fit more aircraft per square foot

- Identifying which hangars have flexibility for transient overflow

Visualizing hangar capacity helps identify both optimization opportunities and problem tenants

Visualizing hangar capacity helps identify both optimization opportunities and problem tenants

The goal isn't just to eliminate hangar queens. It's to maximize the revenue potential of every square foot of hangar space you have.

What This Adds Up To

Every hangar queen represents:

- $3,600-$4,900/year in lost ancillary revenue (for piston aircraft)

- A blocked spot that could serve an active pilot on your waiting list

- Reduced flexibility during peak demand

- Potential maintenance hazards from neglected aircraft

From an FBO's perspective, an airplane that never leaves the hangar might as well not be there at all.

The goal isn't to punish owners going through temporary life circumstances. It's to ensure your limited hangar space is as productive as possible. Active airfields benefit everyone: pilots get well-maintained facilities, FBOs earn enough to reinvest in services, and the local aviation community thrives.

If you've got hangar queens occupying prime real estate while your waiting list grows, it might be time to:

- Audit your lease terms

- Start tracking utilization data

- Have honest conversations with inactive tenants

Curious what better space utilization could mean for your operation?

Run the numbers with our ROI calculator, or grab time with our team to see how other FBOs are tracking aircraft movement and getting more out of their hangars.